Integration (gala.integrate)#

Introduction#

scipy provides numerical ODE integration functions (e.g.,

scipy.integrate.odeint() and scipy.integrate.solve_ivp()), but these

functions are not object-oriented or accessible from C. The

gala.integrate subpackage implements the Leapfrog integration scheme (not

available in Scipy) and provides C wrappers for higher order integration schemes

such as a 5th order Runge-Kutta and the Dormand-Prince 85(3) method.

For the examples below the following imports have already been executed:

>>> import astropy.units as u

>>> import numpy as np

>>> import gala.dynamics as gd

>>> import gala.integrate as gi

>>> from gala.units import galactic, UnitSystem

Getting Started#

All of the integrator classes in gala.integrate have the same basic call

structure. To create an integrator object, you pass in a function that evaluates

derivatives of, for example, phase-space coordinates, then you call the

run method while specifying timestep information.

The integration function must accept, at minimum, two arguments: the current

time, t, and the current position in phase-space, w. The time is a

single floating-point number and the phase-space position will have shape

(ndim, norbits) where ndim is the full dimensionality of the phase-space

(e.g., 6 for a 3D coordinate system) and norbits is the number of orbits.

These inputs will not have units associated with them (e.g., they are not

astropy.units.Quantity objects). An example of such a function (that

represents a simple harmonic oscillator) is:

>>> def F(t, w):

... x, x_dot = w

... return np.array([x_dot, -x])

Even though time does not explicitly enter into the equation, the function must

still accept a time argument. We can now create an instance of

LeapfrogIntegrator to integrate an orbit in a harmonic

oscillator potential:

>>> integrator = gi.LeapfrogIntegrator(F)

To run the integrator, we need to specify a set of initial conditions. The simplest way to do this is to specify an array:

>>> w0 = np.array([1., 0.])

This causes the integrator to work without units, so the orbit object returned by the integrator will then also have no associated units. For example, to integrate from these initial conditions with a time step of 0.5 for 100 steps:

>>> orbit = integrator.run(w0, dt=0.5, n_steps=100)

>>> orbit.t.unit

Unit(dimensionless)

>>> orbit.pos.xyz.unit

Unit(dimensionless)

We could instead specify the unit system that the function (F) expects, and

then pass in a PhaseSpacePosition object with arbitrary units

as initial conditions:

>>> usys = UnitSystem(u.m, u.s, u.kg, u.radian)

>>> integrator = gi.LeapfrogIntegrator(F, func_units=usys)

>>> w0 = gd.PhaseSpacePosition(pos=[100.]*u.cm, vel=[0]*u.cm/u.yr)

>>> orbit = integrator.run(w0, dt=0.5, n_steps=100)

The returned orbit object has quantities in the specified unit system, for example:

>>> orbit.t.unit

Unit("s")

>>> orbit.x1.unit

Unit("m")

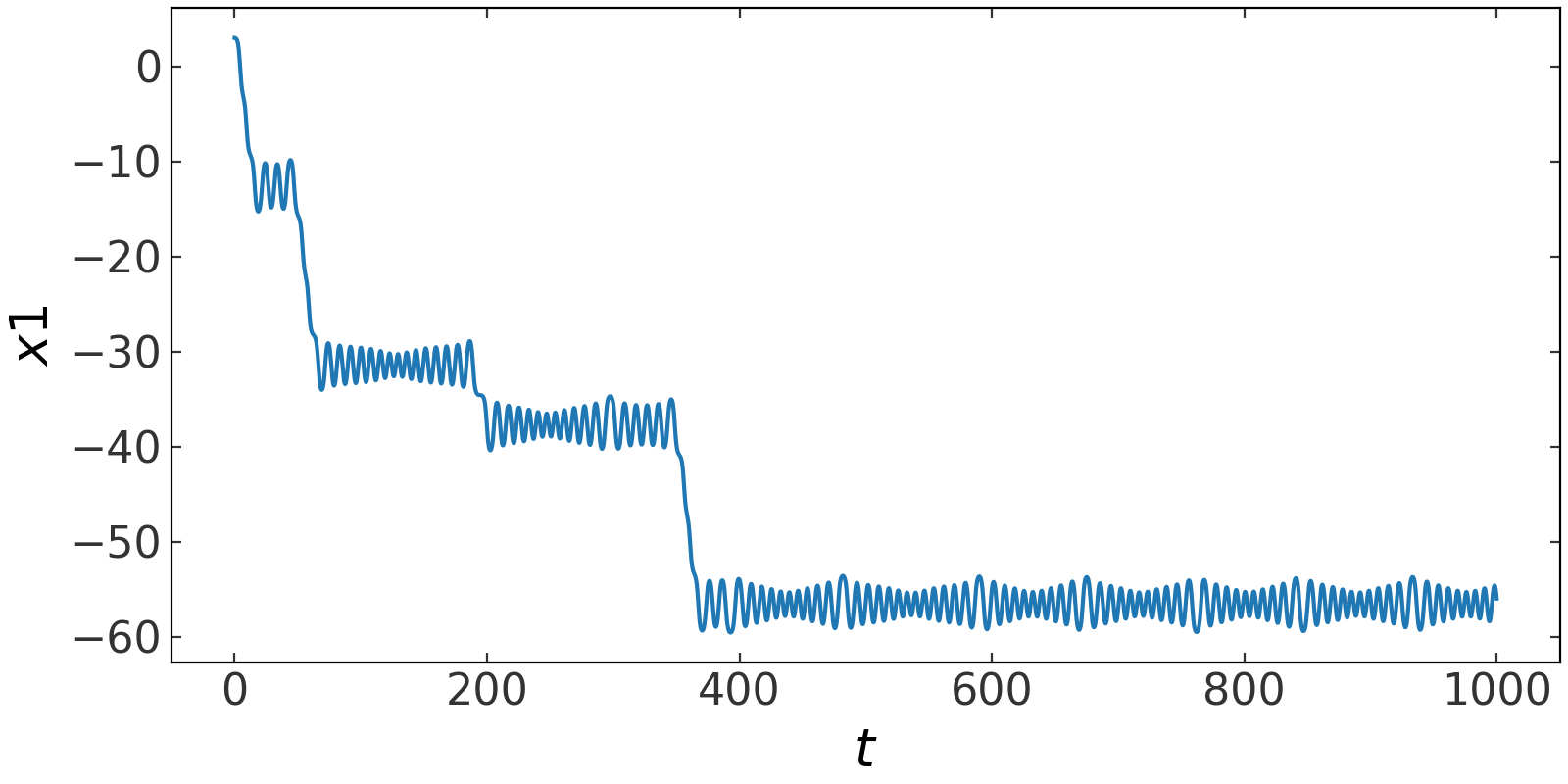

Example: Forced pendulum#

Here we will demonstrate how to use the Dormand-Prince integrator to compute the

orbit of a forced pendulum. We will use the variable q as the angle of the

pendulum with respect to the vertical and p as the conjugate momentum. Our

Hamiltonian is

so that

For numerical integration, the function to compute the time derivatives of our phase-space coordinates is then:

>>> def F(t, w, A, omega_D):

... q, p = w

... wdot = np.zeros_like(w)

... wdot[0] = p

... wdot[1] = -np.sin(q) + A * omega_D * np.cos(omega_D * t)

... return wdot

This function has two arguments: \(A\) (A), the amplitude of the

forcing,and \(\omega_D\) (omega_D), the driving frequency. We define an

integrator object by specifying this function along with values for the function

arguments:

>>> integrator = gi.DOPRI853Integrator(F, func_args=(0.07, 0.75))

To integrate an orbit, we use the run method. We

have to specify the initial conditions along with information about how long to

integrate and with what step size. There are several options for how to specify

the time step information. We could pre-generate an array of times and pass that

in, or pass in an initial time, end time, and timestep. Or, we could simply pass

in the number of steps to run for and a timestep. For this example, we will use

the last option. See the API below under “Other Parameters” for more

information.:

>>> orbit = integrator.run([3., 0.], dt=0.1, n_steps=10000)

We can plot the integrated (chaotic) orbit:

>>> fig = orbit.plot(subplots_kwargs=dict(figsize=(8, 4)))

(Source code, png, pdf)

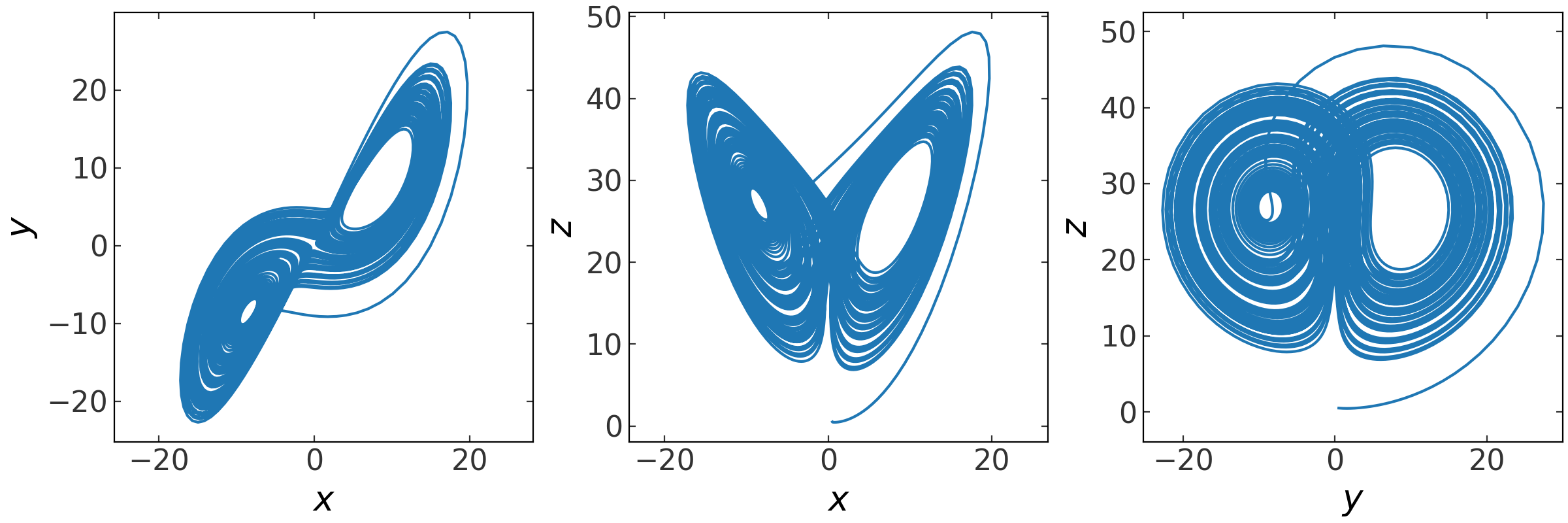

Example: Lorenz equations#

Here’s another example of numerical ODE integration using the Lorenz equations, a 3D nonlinear system:

>>> def F(t, w, sigma, rho, beta):

... x, y, z, *_ = w

... wdot = np.zeros_like(w)

... wdot[0] = sigma * (y - x)

... wdot[1] = x * (rho-z) - y

... wdot[2] = x*y - beta*z

... return wdot

>>> sigma, rho, beta = 10., 28., 8/3.

>>> integrator = gi.DOPRI853Integrator(F, func_args=(sigma, rho, beta))

>>> orbit = integrator.run([0.5, 0.5, 0.5, 0, 0, 0], dt=1E-2, n_steps=1E4)

>>> fig = orbit.plot()

(Source code, png, pdf)

API#

gala.integrate Package#

Functions#

|

Return an array of times given a few combinations of kwargs that are accepted -- see below. |

Classes#

|

This provides a wrapper around |

|

A symplectic, Leapfrog integrator. |

|

Initialize a 5th order Runge-Kutta integrator given a function for computing derivatives with respect to the independent variables. |

|

A 4th order symplectic integrator. |